“The two friends often were mischievous and were repeatedly reprimanded by their superiors. Once, my grandfather ordered a Monopoly board game set for something to do. Charlie had an idea and threw away everything except for the board and the dice and the two of them set it up like a craps table.”

My grandfather grew up in a different era. His name is Paul Carro, Senior. He’s currently in his 70’s and has quite the legacy with five children of his own, in addition to a bevy of grandchildren and great grandchildren. He’s been married to my grandmother, Geraldine for many happy years.

Paul grew up in Norway, Maine, with his mother, Edith. His biological father had left but Paul’s uncle, John, stepped in to fill that vacant spot in the family. John was a solid father figure to my grandfather and he fully believed that he was his biological son. “It was like finding out there wasn’t any Santa Clause,” he told me, in regard to how he felt when he found out that John was actually his uncle. Nevertheless, John had acted the part of the father so well that my grandfather looked past that and treated his uncle like he was his biological father instead. For him, the mere fact that John wasn’t his father by blood did not stop him from enjoying the relationship. Growing up in Maine for him didn’t seem to be easy, or at least not very eventful.

When I once asked about his life growing up, my grandfather laughed, swigging from a bottle of Budweiser as he adjusted his large, square-framed glasses. “Growing up? Yeah, if you wanted to do anything you either walked or rode a bike. If you wanted to watch TV, you’d go to a friend’s house.” Then, he added, laughing and saying with his thick Downeaster accent; “Road kill was a thrill.” I was never quite sure what he meant by that. I laughed along with him and took it as him joking around, as he always did, perhaps implying that road kill made for an entertaining afternoon in his youthful Maine. It wouldn’t have surprised me if it were true. Whether it was embellishment or not, I can’t say, but I know that he did things other than ride bikes or watch road kill. He ran track.

Once, while he was playing baseball, something went wrong with a pitch and the ball ended up striking him in the face. He ended up with a massive black eye out of it and the powers that be at the school told him he wouldn’t be able to play the game for at least three weeks. Not wanting to be idle, he instead tried out for track. He learned to pace himself for a half-mile by running behind a racehorse. In his heyday he’d been an excellent runner. He thinks that he’s lost them somewhere but he used to have newspaper clippings of his achievements along with black and white photos of his grinning track team standing beside him. He’d also garnered three medals; two of them gold, one silver. I remember seeing these items a few times when I was younger and it had been hard to imagine my grandfather, looking toned and svelte in the photos versus the reality of his then-current age. It was a different time, a different Paul.

At one point after he’d been doing track for a while, he was shot in the leg in a hunting accident. To this day, the bullet still rests somewhere inside his flesh, doctors at the time deciding it was best to leave it in there rather than risk taking it out and damaging the tissue further and beyond repair. Despondent, he wanted to give up track all together but his sister Noreen forced him to stick with it and run with her. She would ride her bicycle ahead and cheer him on while he tried to run behind her, hobbling at first but getting better each time until he was back to normal. His eyes often tear up as he recalls this touching moment of kindness and inspiration from his sister, slipping his callused index fingers underneath the lenses of his glasses to wipe away the evidence.

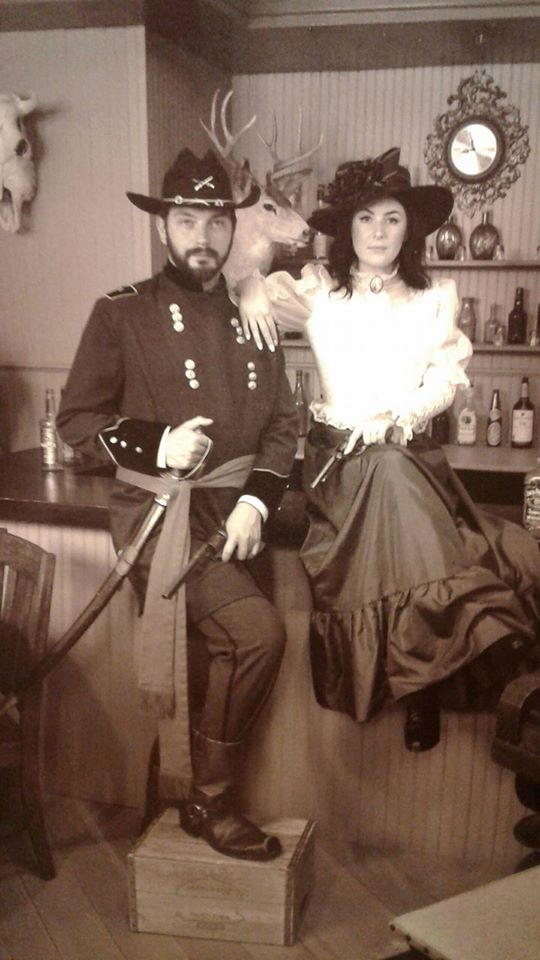

After high school, my grandfather joined the United States Navy. He’d had dreams of working in the science field, trying to find cures for diseases. The entire process interested him and he felt he had some good insight to how the diseases were formed and how they might be treated. He figured that he’d soon be drafted into service anyway, though, so he gave up on his dreams and left his normal life behind for a life in the military. He didn’t give me the details of why he left or how long he was in the Navy, but he enjoys re-telling some of his experiences.

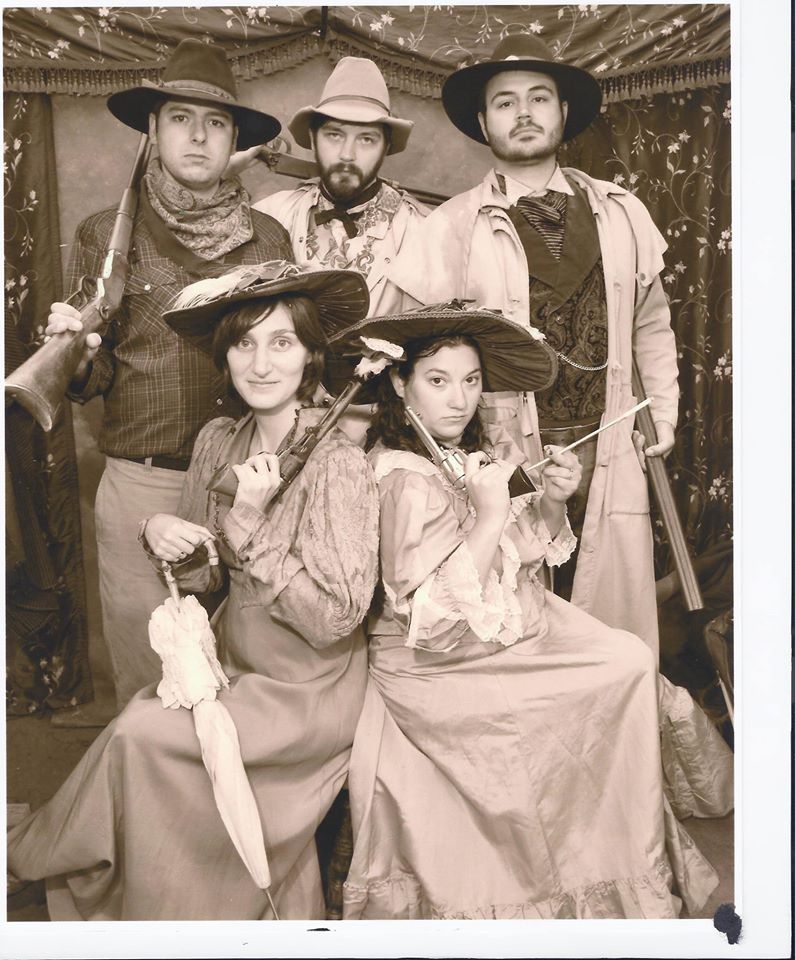

He speaks mostly of a good friend he’d had in the service, a black man named Charlie Todd. The two became fast friends though the time was rife with segregation and an unbelievable amount of racism. Being from rural Maine in the 1940’s and 1950’s, he said he’d never seen an African American and so he thought he wasn’t filled with the same amount of prejudice that the rest of the country was experiencing at the time. When he told the other enlisted men that he was from Norway, they thought he meant the European Norway, so in some ways he felt they didn’t really treat him any better than they treated Charlie because they thought he was an immigrant. A lot of them were openly racist and hung Confederate flags in their rooms or elsewhere.

The two friends often were mischievous and were repeatedly reprimanded by their superiors. Once, my grandfather ordered a Monopoly board game set for something to do. Charlie had an idea and threw away everything except for the board and the dice and the two of them set it up like a craps table. Soon, Paul and Charlie had hustled other naval men out of about $200.00 cash. Word got around and one of the officers came by and put a stop to the game. They didn’t get to keep any of the money, although Charlie tried to hide some in his shoe. It was discovered and the two were punished.

Though he was sort of vague again with the details, my grandfather eventually ended up in the naval hospital. I think it was for a thyroid condition that plagued him throughout much of his adult life, causing him to be sick and to experience fits of rage directed at his children. Some of his children are still upset about it to this day, though in his old age he has calmed down and I have never witnessed any anger like I’d heard about in his past. He seems to have become a different version of his younger self.

While he was in the hospital at the time recovering, he managed to get himself into trouble again. Paul and a few others had gotten their hands on some heavy-duty wax and used it on the floor of their commanding officer’s office, sticking his chair to the floor. Paul was already on thin ice due to the gambling but the commander couldn’t take away any more stripes as he only had one more left, so the punishment was no television instead. During this period of time, my grandfather was only nineteen years old.

One day during the television debacle, Senator John F. Kennedy showed up at the hospital because he was running for president at the time, and making the rounds at military hospitals and bases. He walked through the hospital, shaking the hands of the naval personnel that were there, my grandfather among them. It changed my grandfather’s life, in his eyes. “When I shook his hand, every hair on my arm stood on end,” he said, his aged eyes surrounded by crow’s feet and those thick lenses widening in wonder and awe once more. “He was so charismatic.”

On his way out of the facility, Kennedy glanced at the television and noticed it was off, so he tried turning it on. It wasn’t working. He asked the men around him what was wrong with the TV and, not wanting to stir up trouble with the commander, they feigned ignorance and simply said they guessed it must be broken. Kennedy told the man in charge at the time to get the television fixed right away. Within fifteen minutes, the hospital had a brand new color TV, the first my grandfather had ever seen. Kennedy was the first man my grandfather ever voted for, and when he was assassinated in Dallas, Texas, in November of 1963, my grandfather wept.

After leaving the navy, my grandfather tried to keep in touch with his friend, Charlie Todd. Paul wrote a letter eventually to his friend, who was then living in Philadelphia. My grandfather is not a letter-writing kind of man, but his friendship with Charlie had been so great that its absence in his life after the navy moved him to do so. In the letter, he wrote to Charlie and told him that he should come to Maine to visit him sometime, if he could. He was sent a response letter, but not from Charlie. It was from Charlie’s sister. She explained that her brother had been gunned down in the streets of Philly, victim of a racial crime. Paul wept again.

Even through a lot of darkness he’d gone through early in his life it was not a life totally devoid of light. He had my grandmother, Gerry, to thank for a lot of that. For him, she brings a particular brand of optimism and humor and love to his life. And their entire relationship was founded on a faulty automobile, in days long before Tinder or Facebook or Craigslist.

One day, my grandfather and another of his friends began a contest with each other after seeing rings on display at a pawn shop in Lewiston. They each took a number of rings and decided to see who could give out the most as gifts to women at dances. Apparently the men of that time used to give rings to a girl they wanted to be with, and if the woman accepted, they would begin dating, or at least the prospect of it was open. At least, that’s what I understood from his explanation, though it could have been a regional thing.

Paul participated in the bet but after they went to a dance, he ended up giving away only one ring and then leaving, not feeling up to following through. After he left the dance hall, he ended up not paying attention to where he was going and took a wrong turn, happening upon my grandmother, Geraldine, whose car had broken down on the side of the road. Being the gentleman that he was, my grandfather stopped and tried to get her car to start. After trying for a while, it became apparent that it wasn’t going to start at all, so he offered to give her a ride home. After the ride, he sheepishly asked if she’d like it if he would pick her up for a night of dancing, and again she said yes.

He was happy, and when it came time for him to pick up Geraldine, he arrived at her house late and found that she’d left without him. Thinking he messed it up for good, he went to the dance anyway and ended up dancing with her after all. They danced for quite some time, and had the night of their lives, according to him. The two of them were an item from then on.

In 1973, he started working for Hancock Lumber. He was working there up until a few years ago. He always said it was something he enjoyed doing. He loves people and also loves talking, so he’s a natural salesman. Other people who have witnessed his salesmanship skills are amazed. Fellow employees were extremely impressed with him because Paul had managed to sell two cans of paint to someone who’d just come in to ask for directions. It’s just something that comes naturally to him.

My grandfather may not be the most well-read man, or the best speaker. However, he’s really smart in his own way and has lots to say about life, things he’s tried to impart to me and the rest of my siblings as we’ve grown older. He’s come through a lot of hardships on his own and has a lot of personal demons. He seems to take most of it in stride, however, always telling us that everything is “99% psychological and 1% what you know”. I think he’s right. Because if he’d let the psychological demons get to him in all those trying times, I might not exist. He might never have done the things he did, pushed his body to the limit for track, joined the navy, or asked my grandmother to the dance. He might have let the fact that his dreams of becoming a scientist were dashed get to him, ruining his love for customer service by looking at it as something he was left with and not as something he chose and loved. That 99% that’s psychological is what makes us all unhappy, or…if you can turn it around, happy. It’s what you know that is the constant, that’s in your heart and gut. Let that guide you, as he did. I know that I will try to do the same.